www.sarahmaguires.com

www.sarahmaguires.com As a family with a history of farming in Ireland, my relations are generally quite environmentally conscious, so it’s understandable that some may feel conflicted about their dependency on turf and its impact on climate change. This week, as the weather warms up and we stop lighting the home fires, I want to consider whether it’s time to put out those turf fires once and for all for the sake of climate change. This is a contentious question, but I want to examine it from my personal viewpoint as someone who is both concerned about climate change and nostalgic about the use of turf in our rural heritage.

What is turf?

www.askaboutireland.ie

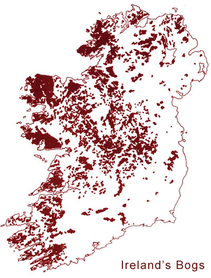

www.askaboutireland.ie By volume, turf land (also known as bogland or peatland) covers around 2% of global land area but represents 50-70% of the world’s wetlands. In Ireland, bogland comprises 15% of our land area (1.125 million ha) and is mainly located in the midlands and western coastal areas.

BordNaMona.ie

BordNaMona.ie Turf was the primary fuel source for heating and cooking in Ireland as far back as the 17th century due to a scarcity of trees. Turf extraction accelerated during World War II as the country faced fuel shortages. Over the last 400 years, turf extraction has resulted in the loss of 47% of the original area of peatlands in Ireland. At present, approximately 9% of our nation’s bog land (100,000 ha) is used for mechanical fuel extraction. 80% of this extraction is done on an industrial scale by Bord na Móna. The remaining extraction is done by privately owned companies. Between 20-38% of harvested turf is burned for domestic use in the form of briquettes or sods, while the majority of extracted turf supplies about 6-8% of Ireland’s electricity needs.

The United Nations classifies turf as a non-renewable fossil fuel since its extraction rate far exceeds its slow regrowth rate. However, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has begun to classify peat as a "slow-renewable" fuel because, in some cases, peat land can regrow at a rate of 1,000-5,000 years if left undisturbed after extraction. In comparison, coal (non-renewable) takes millions of years to form and wood (renewable) takes 3-70 years to reach maturity.

What does turf have to do with climate change?

Cutting turf: When we drain peat lands and cut turf (be it for fuel extraction, compost production, or for land use change to agriculture, forestry, or development), we release the carbon that’s been trapped in that land. It is estimated that Irish peat lands store 64% of the total soil organic carbon present in Ireland. Because Ireland has one of the highest percentages of peatlands in Europe, we have a unique, natural carbon sequestration resource to mitigate against climate change and greenhouse gas emissions if we preserve peatlands in their natural state.

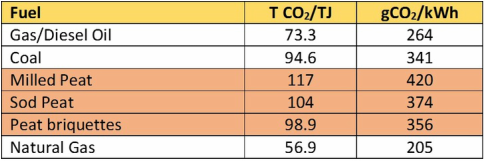

Burning turf: When we burn turf, we release further carbon from the turf into the atmosphere. In fact, turf is the worst of all fuel sources with respect to its greenhouse gas emissions and impact on climate. It has higher carbon dioxide emissions per unit of energy than any fossil fuel source (e.g. coal, gas). In addition, the calorific value (or heating potential) of milled peat is only one quarter to one sixth that of coal and about one tenth that of oil, so it burns less efficiently than any fossil fuel source. The only advantage peat has over coal as a fuel source is that it produces less smoke and has a lower sulphur content, thus resulting in less air pollution.

Is there a climate-friendly alternative to turf?

Drury Forest 2014. Photo credit: Cara Augustenborg

Drury Forest 2014. Photo credit: Cara Augustenborg The obvious alternative to burning turf in Ireland is wood. While burning wood still releases carbon dioxide, it’s considered carbon-neutral because the rate of tree growth (and the carbon dioxide those growing trees take in) offsets the carbon that’s released upon burning wood. Wood also has almost no sulphur compounds in it and is therefore better for air quality than turf or fossil fuels. The energy density of dried wood (15-18 MJ/kg) is similar to turf (15-17 MJ/kg), so wood can provide similar heating capacity as turf (per unit weight) without the impact on climate and environmentally sensitive boglands.

With respect to price, wood fuel is also cost-competitive. The latest fuel cost comparison from Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland (2015) indicates peat costs 6.87 cents per kilowatt hour, while wood ranges from 5.99 to 8.02 cent/kWh depending on how it’s packaged. Wood fuel industries also create long term jobs in Ireland, many of which are in rural communities currently suffering social and economic decline.

Does turf make economic sense?

Photo credit: National Peatlands Strategy

Photo credit: National Peatlands Strategy It’s worth noting that even Bord Na Móna has found conditions for peat harvest more difficult recently. Their 2013 annual report states:

With this week’s announcement by Oxford University professor, Myles Allen, that the risk of extreme storms on the west coast of Ireland is now up 25% due to climate change, peat harvest may become increasingly difficult and less economically viable for all turf cutters in our future Irish climate.

In the meantime, those of us that have to pay for our household heating fuels have a choice to make with respect to which fuels we burn. The evidence I’ve provided demonstrates that turf makes the least environmental and economic sense of all our household fuel options. You could even argue that turf has both the disadvantages of a fossil fuel and a renewable fuel without any of the benefits of renewable fuels. Like fossil fuels, turf is essentially non-renewable (taking thousands of years to form) and produces larger carbon dioxide emissions while having a much lower heating capacity compared to any fossil fuel. Like many renewable fuels, turf harvesting is a seasonal activity and thus dependent on weather conditions. In fact, its dependency on fair weather is higher than any renewable fuel, making it a risky fuel source to invest in given projections for future climate change.

The National Peatlands Strategy argues that turf extraction provides jobs for the rural economy and is part of our national heritage, but the reality is that turf extraction made economic sense when we had no other choice. Rural jobs can be created just as easily from renewable fuel industries, and our cultural heritage as a once forested nation is as valuable as that of our heritage as turf cutters, who had no better alternative than to drain our natural bogs. A prosperous future for Ireland cannot be based on an inefficient fuel source.

Conclusion: Is it time to quench our turf fires?

My late grandmother, Margaret Lynch (nee Brosnan) of Kilflynn, Co. Kerry

My late grandmother, Margaret Lynch (nee Brosnan) of Kilflynn, Co. Kerry My Grandmother, Margaret Lynch, would have been 105 years old this week. Despite being a native of Co. Kerry, she lived in London during the World War II bombings and became a skilled conservationist as a result of rationing and lack of resources. I can’t look at a turf fire without thinking about her and how comfortable she made me in her home, but times have changed from the days when all my granny had to burn was turf. I’m sure that if she had a more efficient fuel alternative, she wouldn’t have hesitated to use it based on her practical, resource-efficient nature.

As individuals, we may feel we have limited power to stop the large scale extraction of peat in Ireland despite the fact that it makes no economic or environmental sense. However, we have enormous purchasing power in what type of fuel we use in our homes. As a result of my research for this Climate Friday FAQ, I’ll be using my own purchasing power to quench my turf fire once and for all. I hope some of you are inspired to do the same.

Keep fighting the good fight!

-Cara

RSS Feed

RSS Feed