In my humble opinion, the one day of the year that Ireland discusses environmental issues should be far more inclusive. I decided to use 15 seconds of my time at the podium to see how many of the 250+ audience represented a civil society group -Less than 15 people raised their hands. Most NGO representatives wouldn’t be able to afford to come to this kind of conference, so I felt the need to bring that minority perspective to the table.

I was asked to speak on “a vision for a fossil free society by 2050” -essentially a repeat of my TEDxUCD talk, but it’s been nine months since that talk and we’ve had COP21, our own climate legislation and a new government in the meantime. It was time for an update with a much needed reality check on where we are in achieving that vision. Unlike my TEDx talk, which was designed to inspire the public to “just ask” for climate action, this talk was less about asking and more about getting them to choose which side of the fence they want to be on: standing idly by our government trying to do as little as possible or mucking in and transforming Irish society in line with the rest of the world. Listen to my #EnvironmentIreland16 talk on Sound Cloud or read my transcript below. A vision (and reality) of a fossil free Ireland by 2050

If we’re serious about keeping the Earth’s temperature under 2 degrees Celsius of warming above pre-industrial temperatures, we need to become a fossil free society by 2050. That’s only 34 years away, so hopefully many of us will still be around to witness that dramatic evolution from our industrial, fossil-fuel driven past to a new fossil fuel free society. We are the transition generation.

People perceive climate action as involving more taxes and a reduction in their quality of life. For example, last year RTE Prime Time’s debate on climate change asked the question “will fighting climate change cost Ireland money?” but we never hear a debate on how much it will cost Ireland if we fail to act.

Incidentally, we’ve already spent over 150 million per year over the past two years just in flood repairs and insurance pay outs from our wetter, stormier winters, and you may recall the delayed spring in 2013 that contributed to our fodder crisis cost us 500 million euro. When you put what we need to do to address climate change into simple terms, essentially to keep 80% of the world’s known fossil fuel reserves in the ground and stop exploring for any more oil and gas because we can’t burn it anyway -what you find is that the things we need to do to end our dependency on imported fossil fuel and peat are all things that would actually improve our quality of life.

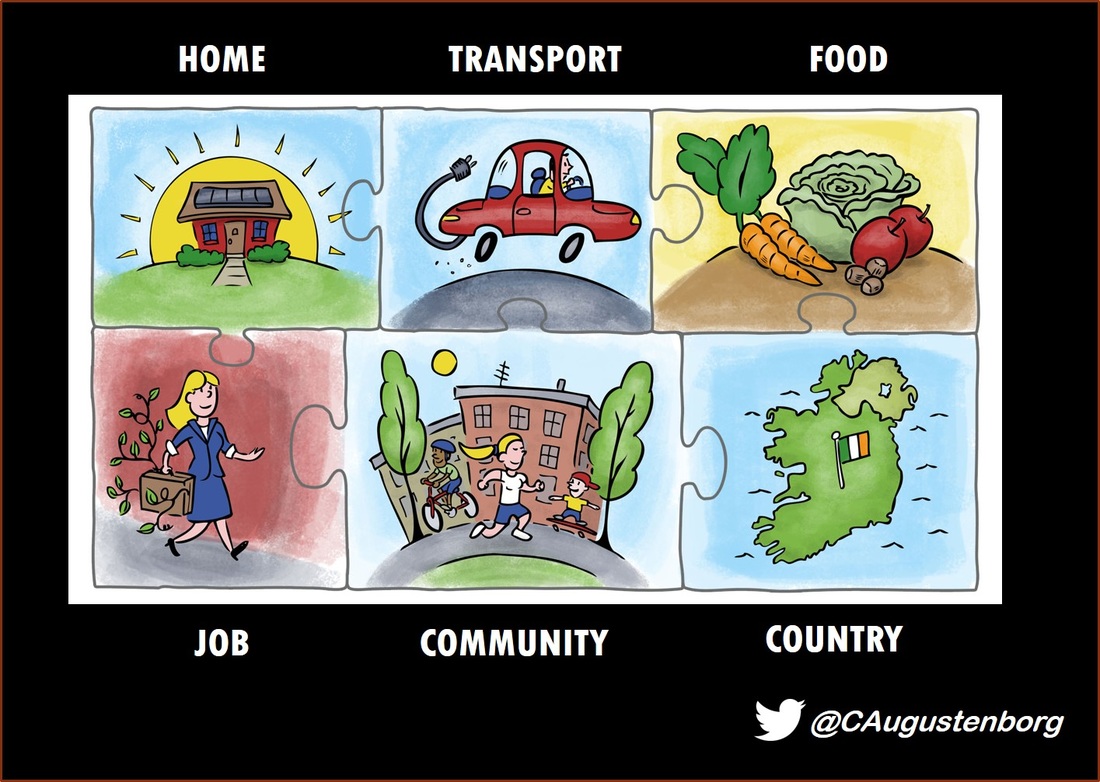

Home

We saw our first A- rated passive housing estate open in Enniscorthy last April with houses that have a typical energy bill of EUR 200/yr compared to 2500/yr from conventional homes. Developers are already responding to future policy changes and consumer demand.

We have the vision, but we still have two million existing homes in need of retrofit and need a new national renovation strategy to tackle this -which the EU requires all member states to have by April 2017. At an average cost of EUR 28,000 per home for deep energy retrofit this is a significant technical and financial challenge, but an essential part of achieving a fossil free vision for Ireland. Transport

The last Fine Gael-led government rolled back on the previous government’s car taxation scheme based on emissions, and now a quarter of our vehicles are SUVs and we have some of the highest diesel car sales in the world. No one pays for the extra costs these kind of vehicles incur not only in terms of their emissions but also their impact to air quality, public health, and the additional wear and tear on infrastructure that larger vehicles can inflict.

We need to set ambitious milestones to ensure we make the EV transition – like The Netherlands, where they’ve prohibited the sale of diesel or petrol vehicles by 2025 so they go from 10% EV purchase to 100% in less than 10 years. Or California, where they just legislated an emission reduction target that will have the most car-mad state in the USA reach 25% EV ownership and 50% renewable energy production by 2030. If we’re heading toward a fossil free Ireland, we need to discourage the purchase of the least fuel efficient vehicles and roll that money into incentivising electric vehicles, but our fossil free transport system cannot be based on electric vehicles alone. Our LUAS carries over 35 million passengers a year with continually increasing demand and need for expansion. It’s an example of the right approach to public transport. More of this, please! We also need to begin decarbonising our buses. In Sweden, 2/3rds of their buses are already ethanol powered. In the UK, the first buses powered by human and food waste went into service last year. Prof. Jerry Murphy at UCC has done lots of interesting research for over a decade on how we could power our buses from livestock slaughter waste, municipal waste, and even sea lettuce. Prof. Murphy spoke to the Oireachtas about many of these options in 2008 an urged them to ensure any new buses could run on alternative, indigenous and renewable fuel sources and yet no changes have been made. The technology has all been there for a while now. All that’s missing is the political will to make it happen.

Cyclists.ie and Dublin Cycling Campaign have worked tirelessly on a volunteer basis to work with our National Transport Authority to create safer cycling infrastructure and encourage more cycling. In Copenhagen, 45% of the population uses bikes for their daily commute, while in Dublin we’re at less than 6%.

We need more cycle paths like the one along the Grand Canal and a policy that we only build cycle paths that are safe enough to let our kids ride on. That takes investment but last year we spent less than 1.5% of our transport budget on sustainable transport (mostly in the form of safe cycling education for kids). We need to spend about 10% on actual cycling infrastructure if we’re serious about the low carbon transition. The EPA reported last May transport emissions will increase 13%-19% on current levels by 2020. If we want a fossil free Ireland, we need to break the transport silence and start asking hard questions about how transport really will contribute to the low-carbon transition. Food

It is challenging to reduce emissions from agriculture but by no means impossible. Even Teagasc has declared Ireland should aspire to carbon-neutrality in the sector and that aim is part of our National Policy Position on climate action.

We have strengths that offer us opportunities to become leaders in addressing the challenge of climate change in the agricultural sector, including the fact that most of our dairy and beef farms have calculated their carbon footprint under Origin Green and that our carbon efficiency per unit of beef or dairy is lower than most other countries, but these facts are not enough to claim leadership. To lead in climate smart agriculture, we need to reduce absolute emissions because the Earth simply doesn’t care how carbon efficient our beef or dairy is. -All that matters is how much more total carbon we pump into our finite atmosphere. Last December, I went to Athlone with RTE’s Ear to the Ground and met dairy farmers who were suffering their second flood in five years. They told me how they’d raised their sheds 18 inches after the 2009 flood at considerable expense only to be standing in a further 12 inches of water last December. They told me how they didn’t know if they could keep farming under these conditions. Last December was a moment where I thought we were change ready. The Climate Summit had just happened and there wasn’t a Minister in Ireland that didn’t stand in those flood waters and tell us we could expect to see more of it due to climate change. But it’s been nine months and we’re no better prepared for the next flood. We should be encouraging our farmers to diversify out of volatile dairy markets and unprofitable beef to protect themselves from future climate change. We should be helping them to contribute to the renewable energy transition by putting a price on solar and facilitating them toward a solar rooftop revolution. We should be paying them to become our first flood defenders to slow water down upstream and protect populated towns and villages downstream as they’ve done in England and Wales. This is a vision of Irish agriculture that would see our communities much more connected to our farmers and local food. Our reality is that EPA projects our domestic agricultural emissions will increase by at least 2% between now and 2020. Teagasc recently published a scientific paper in the Journal of Land Use Policy that concludes it is highly unlikely that the Food Harvest 2020 ambition and climate objectives are compatible, and stated this may necessitate a reappraisal of the Food Harvest targets. This is the policy intervention that’s required if we want a fossil free Ireland. Jobs

One of my favourite examples of this comes from Prof. Jerry Murphy again who determined we could run 150 city buses just on the organic leftovers from Irish Distiller’s whiskey.

More recently, I met a team at UCD led by Colin Keogh and Tom Curran who are using waste plastic bottles as the filament to go into 3D printers for new plastic products. This is the kind of innovation and new job creation a circular economy can bring. IBEC supports this new model, but advises that we need a revised waste policy to make it happen. Incineration sends us backwards on the circular economy and sustainability pathway by decades. We’re already losing out on jobs because we’re not making this transition fast enough. Last week, a bioenergy company, Solar 21, announced it had sent 80 jobs destined for Ireland (and potentially hundreds more) to the UK because our energy policies were not progressive enough. Community

We’ve all learned a painful lesson about the need to involve communities in the low-carbon transition. Many parts of Europe are experiencing a revolution in community ownership of renewable energy, but we still have no community feed in tariffs on solar and risks on wind ownership are substantial so community involvement in the low-carbon transition is depressingly limited. This is an issue Friends of the Earth Ireland has invested considerable time into over the past few years, trying to remove the red tape for community owned power.

Ireland has learned a painful lesson in wind development. My colleague, Craig Bennett, Director of Friends of the Earth England, said it best when he described how essential it is to engage communities when he wrote in the Guardian the day after Brexit. He said:

This is critical in creating a fossil free Ireland.

To date, we haven’t involved people in this transition. We really shouldn’t just be having these kind of conversations among ourselves. We should do more to engage all of society in this challenge starting with making conferences like Environment Ireland more accessible to civil society groups. Country

The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre estimates an average of 22.5 million people have been displaced each year by climate or weather-related disasters in the last seven years - equivalent to 62,000 people every day.

In Bangladesh, almost five million people have left their rural homes to live as "pavement dwellers" in Dhaka due to flooding, storms and a dramatic decline in agricultural productivity. That number is growing at a rate of half a million people per year and Dhaka will soon become the largest megacity in the world. Surely, this is the kind of suffering and hardship Enda Kenny was referring to in his impassioned speech at the U.N. last September. But we are one of only two countries that will not meet its EU 2020 targets. In fact, we’ll fail to miss them by about 70% and our failure has now become a convenient argument for lower 2030 targets. In other words, for the next two years there is no incentive for Ireland to make any efforts to reduce emissions that would only make 2030 targets more difficult to achieve in the future. This is not the behavior of a country that is compassionate to the hardship of others. Nor is this the behavior of a country who cares about helping its future inhabitants to be energy or food secure. The "Think" versus "Do" gap

The mismatch between the ambition for climate action that we saw in Paris and in our own climate legislation compared to the evidence that our government has no plans to achieve a fossil free Ireland by 2050 has never been more clear. If anything, their efforts to date will delay such a transition.

Each of us now has a choice to make. Do we want to put our efforts into making the transition or stopping it? Fortunately, there are countervailing forces in Ireland that are still working toward a transition: Global players, companies like Diageo; The renewable energy sector; local communities who want community-owned power; and even our esteemed climate advisory council, who has the opportunity to consider the National Policy Position on climate action that aims for an 80% decarbonisation in buildings, energy and transport and carbon neutrality in agriculture by 2050 when providing recommendations to government. Change happens in the blink of eye

Carbon Tracker’s Mark Campanale presented two images to the audience of Trocaire’s Investing Ethically conference earlier this year. Both images were of 5th avenue in New York during an Easter parade, one taken in 1900 and one in 1913. On the left, you would struggle to find a car in the photo as the transport is dominated by horse drawn carriages. On the right, only 13 years later, you can no longer spot the horse.

The photos illustrate that while we may have difficulty imagining a future different from today– a vision of a fossil free Ireland in 2050, change happens quickly, particularly when new technologies like cars and mobile phones cause market disruptions.

In the mid-1980s, AT&T forecast cell-phone adoption by the year 2000 to reach 900,000 subscribers. The actual number was 109 million and AT&T missed out on a multi-trillion dollar opportunity. We are seeing similar disruptions in solar and in electric vehicles now. We may perceive that nothing ever changes, but when it does it happens in the blink of an eye, so we can no longer sit on the fence while the rest of the world leaves us behind.

Now I see blogging as part of the reinvention of democracy. We're no longer beholden to conventional media to give us a platform. Today, everyone has a voice via the world wide web, and if our words are compelling, people will spread them and help change hearts and minds.

Blogging also allows us to write in a far more personal style than most other types of writing, a style that is sorely lacking from most environment and climate communication. It took the scientist in me a while to shed my technical skin and let rip, but now that I have I'd find it hard to go back. We're only human and it's natural to need personal stories to connect to a complex message. We need to understand that environment and climate are not separate from us. Thank goodness blogging has finally given us a style to convey that essential concept. On a personal level, blogging has become quite therapeutic for me. When the "good fight" has gotten me down, I've found myself taking to the web to vent frustrations. In that virtual world, I find like-minded people who echo my feelings and encourage me to keep going. At times, we join forces and become stronger through collaboration. I doubt I would still be active in climate campaigning if it weren't for that global network of virtual support. The task would simply feel too big and lonely. Ironically, when I re-branded my blog six months ago from 'Cara's Climate Friday FAQs' to 'The Verdant Yank' it was partially out of frustration for always feeling like an outsider in Ireland despite having Irish citizenship since birth and living here longer than any other place in the world. No matter how hard I tried to prove my Irish-ness, I was repeatedly rejected professionally on the basis of my American accent and Danish last name so I decided to finally own the label and accept my place as an outsider. I assumed being a 'Yank' would preclude me from winning an Irish blog contest, so thanks to the organizers for making this Yank feel Irish for a change! That feeling of belonging, acceptance and validation for voluntary efforts couldn't have come at a better time. Congratulations to all my fellow 2016 Blog Award Winners, who I really enjoyed meeting and being inspired by at #LWIBloggies2016, and extra special congratulations to my colleagues at GreenNews.ie who won the Science and Education corporate category. Two environmental blogs winning this year's competition means more than just a personal win for The Verdant Yank, but a bigger win that demonstrates public interest in environmental issues, and that gives me warm fuzzies....

To make matters worse, very little (if any) of the waste generated at music festivals is usually recycled. Generally, the waste from Electric Picnic is incinerated. While on the surface that might appear to be a better option than landfill, incineration has a host of problems:

Nonetheless, any recycling is better than none and we learned valuable lessons along the way to improve next year if given the chance. Personally, I learned the battle against waste is just one big communication problem. We need to standardize our recycling rules, bins, symbols, and colors nationally and even internationally so that people hardly have to think when they sort their waste.

The biggest lesson I learned at Electric Picnic was that winning the battle on waste starts with incentives. Friends of the Earth ran a plastic cup and bottle refund station on behalf of Electric Picnic and Festival Republic, paying out 20 cents for every cup that was returned. Last year, they paid EUR 12,000 to those who returned cups. This year, popularity of the refund scheme surged, particularly among kids. One “eco-entrepreneur” earned over EUR 1,000 in refunds, covering the cost his festival ticket and leaving him with more than EUR 700 in spending money! In total, EUR 31,000 was given to those who returned cups. Over 150,000 cups stayed out of an incinerator and the arena grounds were practically devoid of plastic as a result. Every Can Counts ran a similar incentive scheme for tin cans at the Picnic, offering guests a raffle ticket for passes to next year’s festival for every bag of tin cans they returned. Hard core beer drinkers were glad to have another excuse to fill as many bags as possible, and the number of tin cans littering the campsites was (I’m told) lower than previous years. Incentives are key, and we need to start at the source of the problem. The festival organizers were keen to Green the picnic and put food vendors on notice to supply fully compostable packaging, which would have dramatically reduced the waste stream. From my own walks down the 'food mile', it seemed very few vendors adhered to this rule. Nor did vendors take any responsibility for keeping the area around their stalls clean. If I were organizing Electric Picnic, I’d start by incentivising vendors to improve packaging and littering by awarding a free stall at a future festival to the most eco-conscious vendors. I’d turn the Green Messengers into a roving judging panel based on their new expertise. Most people go to Electric Picnic to hear good music. I went to learn about waste. While the amount of rubbish and the public disregard for proper disposal was pretty depressing, I saw opportunities for dramatic improvement given the right support from organizers and waste collectors in combination with a stellar group of enthusiastic volunteers who genuinely care about recycling. In spite of the mess left behind, I was proud to have been a part of something that made at least a small, tangible difference to the environmental footprint of Ireland’s biggest music extravaganza. Here’s hoping it’s a step in the right direction and a sign of bigger things to come.  Keep fighting the good fight! -Cara

|

Archives

December 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed