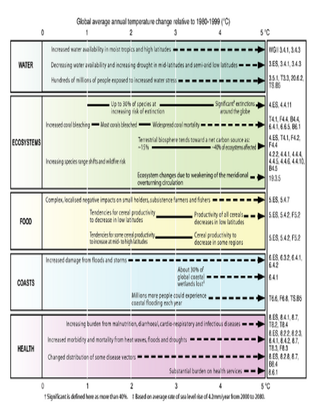

| In 2010, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) set an international policy goal to keep global warming below 2°C to limit the dangerous impacts of climate change. Some of the impacts that may occur if we exceed a 2°C increase in Earth’s average surface temperature include:

|

A Climate Friday FAQ reader’s question

What are feedback loops?

www.thisbluemarble.com

www.thisbluemarble.com “Even if we stay under 2ºC, could that trigger feedback loops that send us over?”

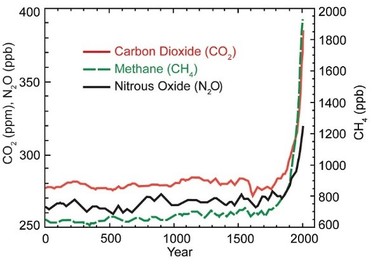

Excluding slow feedback processes was appropriate for climate models of the last century when conditions were more stable. However, in order to predict warming for the 21st century and beyond, Hansen argued that slow feedback processes must be considered because their “instigation is related to the danger of passing ‘points of no return’, beyond which irreversible consequences become inevitable, out of humanity’s control”.

The short answer to Jonathan Victory’s excellent question is yes. - Even if we keep our greenhouse gas emissions low enough to stay under 2ºC, feedback loops could cause temperatures to increase further and send us over 2ºC. Our climate models do not account for slow feedbacks and some of the fast feedback modelling (e.g. cloud formation) is still uncertain. If we aim for 2ºC limit based on current models, in the long term (after 2100) the slow feedback processes could result in further warming of 4ºC or more, which would make life very difficult for those who have to try to exist on such a planet.

What does this mean for us?

People's Climate Ireland and Young Friends of the Earth campaigning on Global Divestment Day 2015

People's Climate Ireland and Young Friends of the Earth campaigning on Global Divestment Day 2015 We’ve seen from IPCC reports that even 1.5ºC of warming will cause significant ecological impacts and that warming beyond 2ºC is unsafe for humanity and our ecosystems. Keeping our earth’s temperature below 2ºC is still possible if we reduce global greenhouse gas emissions by at least 40-70% by 2050 and near zero emissions by 2100.

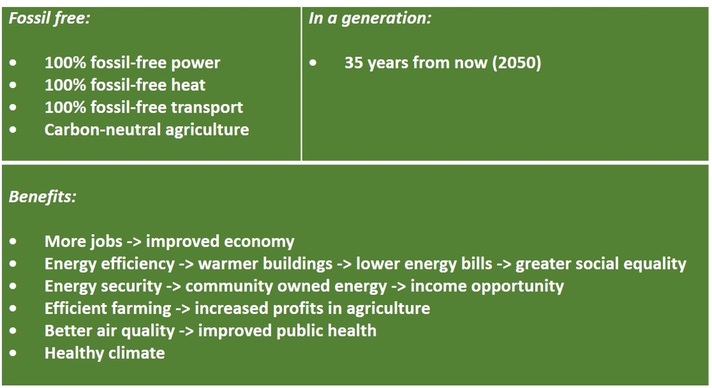

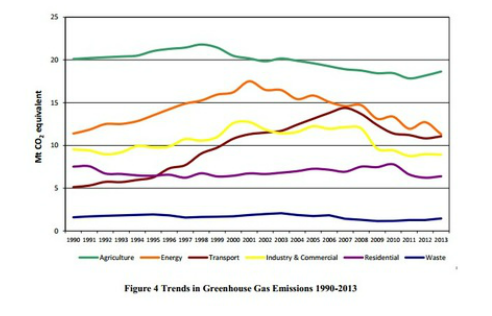

The scientific evidence on the extent and impacts of warming is the reason we need full “decarbonisation” of our society to completely cut our dependence on carbon-based fossil fuels. Moderate emissions reductions will not stop runaway climate change. That’s why many of us get angry when we hear leaders paying lip service to climate action without putting real work into transforming our society. That’s why organisations like the Green Party are fighting for Ireland to become “Fossil Free in a Generation”. Whether we’re trying to keep Earth’s temperature from increasing 1.5ºC or 2ºC, we’re still a long way from achieving either at the moment and the planet’s feedback processes will only further accelerate warming. The longer we wait to take action, the more expensive and harder it becomes to stop runaway climate change.

Thanks for the great question, Jonathan.

Keep fighting the good fight!

-Cara

Stay tuned next Friday for FAQ #6 - based on my upcoming talk at Dublin City University's Communicating Climate Change seminar on Thursday, March 5th. Hope to see some of you there!

Feel free to contact me through e-mail, Twitter, or Facebook with any climate-related questions you’d like to see addressed in future posts.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed