Cara Augustenborg speaking at Climate Conversations 'A New Economy' event, March 26, 2015, Trinity College Dublin

Cara Augustenborg speaking at Climate Conversations 'A New Economy' event, March 26, 2015, Trinity College Dublin  bbc.co.uk

bbc.co.uk Low-carbon economy: A low-carbon economy is another term for a decarbonised economy or a low fossil-fuel economy, meaning an economy that is based on low-carbon power sources (e.g. renewable energy sources or nuclear power) and therefore has minimal greenhouse gas emissions and impact on climate change.

Why should we move to a low-carbon economy?

rte.ie

rte.ie - More jobs - Renewable energy generates more jobs than fossil-fuel based energy production. For example, one model indicates an increase of 91-119% in employment if the United States switched from coal/gas to renewable energy production. In Ireland, the sustainable energy sector already supports over 15,000 jobs.

- Greater social equity - Fuel poverty now affects approximately 300,000 households in Ireland. Spiraling energy costs impact poorer people more than the middle-class or wealthy. Renewable energy and community ownership schemes enable cheaper, more stable fuel prices which can improve social equity between classes.

- Improved national fuel security - Removing dependency on foreign imported fossil fuels improves our national security and foreign investment potential. To date, we have saved over one billion Euro in fossil fuel imports in Ireland through renewable energy production.

- Improved agricultural production - Carbon mitigation strategies can improve soil tillage and lead to increased agricultural productivity. Expansion of sustainable bioenergy crop production can also open up new markets for farmers. Furthermore, low carbon farming is more efficient and cost-effective, ultimately making farms more profitable.

- Improved public health - Fossil fuels release particulate matter and harmful chemicals when burned. Switching to clean, renewable energy sources eliminates these substances from our air and improves public health and associated costs. One study indicates that switching to a low-carbon economy could prevent 5,000 premature deaths a year in the city of London alone.

Ethiopia - phys.org

Ethiopia - phys.org - Costa Rica has just achieved a record-breaking 75 days on completely renewable energy sources and hasn't burned any fossil fuel for energy production since December 2014.

- Denmark is well on their way to achieving a low carbon future, with residents in Copenhagen already producing half the greenhouse gas emissions of the OECD average.

- Some of the world's least developed countries (such as Ethiopia, Bangladesh, and Bhutan) are leap-frogging the old carbon-based economic model in favour of the new low-carbon economy, in a similar fashion to the way they embraced mobile-phone technology instead of land lines.

Carbon's current state-of-play

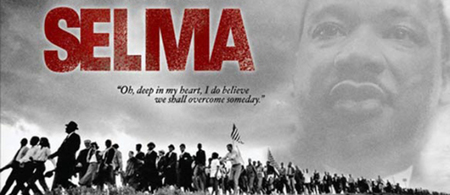

The technology already exists for Ireland to become a low-carbon society in the next 35 years. If you want the proof, read my Climate Friday FAQ #3 where my research led me to the conclusion that the only obstacle to becoming a low-carbon Irish society by 2050 is the will to make it happen. The challenge is how to inspire the public or political will to move away from unsustainable economic growth to a new economic model.

You would think that given our recent economic collapse we’d have an easy job convincing people to prioritise an economic transformation and prevent the mistakes of the past from happening again, but if you read the 2015 Action Plan for Jobs and the uninspiring section on Green Economy, it’s evident that the government still has not accepted the need for a new economy that’s based on sustainable economic, social, and environmental growth.

Two small steps for man

There's capital in nature - greenbiz.com

There's capital in nature - greenbiz.com Thinking beyond low-carbon: Those of us in the climate change arena talk about the need for a "decarbonised economy" or a "low-carbon economy" because this is critical to stop runaway climate change. However, to be successful in achieving this low-carbon economy, we have to reach out to our colleagues working in other sectors such as biodiversity and agri-environment. There is an extensive amount of work already done by groups like the Irish Environmental Network and the recently formed Irish Natural Capital Forum demonstrating the economic benefits of nature and the higher employment potential of a green economy over our traditional economy. It seems obvious to me that a society producing its own renewable energy independent of fossil fuel imports is going to be far more stable and have higher employment and investment potential than our current system, but a new economy needs to focus on more than just decarbonisation and consider the economic and social capital of all our natural resources.

The role of education: Since last night's Climate Conversation took place in an academic institution, it seemed fitting to highlight one small but critical way we could improve the acceptance of a green economy in Ireland and that’s through education. I was educated in the USA - In many MBA programs and business schools there, you’ll find a “business and environment” course where students can learn about how business impacts the environment and how to make informed decisions about doing the right thing socially or environmentally even when it costs more. I took such a course in UCLA's MBA program and it transformed the way my classmates and I viewed the world and approached our careers. In 2009, Bloomberg Business Week published an article about the surge in green MBA programs. That article ended with the statement:

“Broader views of how business impacts the environment will start with business schools...Future MBAs will have to be green to earn green.”

The concept of environmental sustainability and the green economic model in the business schools of Ireland is long overdue. Our future business leaders must be equipped with a fundamental understanding of environmental sustainability to operate in our emerging low-carbon/green economy.

Two giant steps for mankind

nasa.gov

nasa.gov Ireland's Climate Bill: For over a decade, the environmental NGOs in Ireland have been working toward the publication of legislation on climate to "provide certainty surrounding Government policy and provide a clear pathway for [greenhouse gas] emissions reductions". Its significance may not be apparent to many people, but because we have no legislation on this issue so far, our government departments have sat on the fence with respect to climate action. Passing legislation on climate will force each government department to be accountable for emission reductions. More importantly, Ireland's climate legislation is centered on "Climate Action and Low Carbon Development" which could lead to both emission reductions and an overall transformation of our society to one that is fossil free by 2050.

Last night, I planned to say that the if the Climate Bill was revised to define what low carbon actually means, then this legislation had the potential to legally push Ireland towards a low-carbon economy. However, as of this week, Minister Alan Kelly rejected the recommendations from the Joint Oireachtas Committee on the Environment, Culture and the Gaeltacht (including his own Labour backbench TDs) and has refused to include a definition of low-carbon in the bill. Furthermore, this government has now revised the timelines in the bill to ensure that there will be no action on climate while Fine Gael and Labour remain in government. Without a legally upheld definition of low-carbon, Ireland has no obligation to move towards a truly low-carbon society. I try to keep this blog relatively unemotional, but the more I think about the Minister's response to the Climate Bill this week, the angrier I get. If you needed proof that this government doesn't give a toss about our environment or our long-term economic sustainability, the fluff that their calling a "climate action and low carbon development" bill is clear evidence. What could have been an opportunity to move Ireland in step with the rest of the world by transitioning to a low-carbon society has become a nothing but a box-ticking exercise so that Fine Gael and Labour can carry on with business as usual.

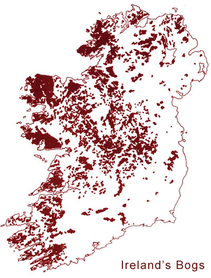

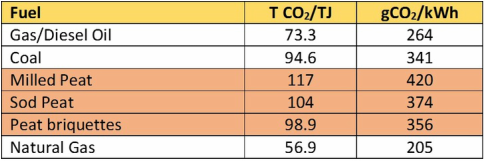

Ireland's energy policy: Our remaining hope toward transitioning to a low-carbon economy lies in the upcoming White Paper defining Ireland's energy policy for the next seven years. A core component of a low-carbon economy is a zero-carbon energy supply. While renewable energy provides 20% of our current energy requirements and is continuing to expand, this movement toward a low-carbon energy sector is partially offset by a projected 19% increase in coal combustion by 2020, continued peat extraction, and by the Department of Communications, Energy and Natural Resources ambition to prioritise oil and gas drilling over the next five years. The White Paper (due for publication in September 2015) has the potential to make the low-carbon transition an over-arching vision of Ireland's energy policy. Citizen lobbying to Min. Alex White on this issue right now is essential to ensure that happens. If the White Paper does not include aggressive strategies to move toward a zero-carbon energy supply, we delay movement to a low-carbon society by another seven years and Ireland becomes even less competitive in the global economy.

Conclusion: How do we move to a low carbon economy?

Keep fighting the good fight!

-Cara

RSS Feed

RSS Feed